Public Sector Debt Management

August 2017

Policy Issue

During 2008-2011 the Labour government successfully implemented countercyclical fiscal policy to moderate the impact of the global financial crisis.

As a result of the fiscal deficits in those years the net public debt rose from £520 billion in April 2007 to just over £1 trillion by the general election of 2010.

By June 2017 despite the austerity rhetoric of the subsequent coalition and Conservative governments the debt reached £1.75 trillion.

Is this level of debt a problem requiring action by an incoming Labour government? Need the debt be reduced and is it a burden on current or future generations?

Analysis

1. The UK government has the tools to prevent debt default and excessive interest rates. These are not and will not be problems.

Britain has a national currency managed by a national central bank. As a result the British government can never default. It can replace maturing public bonds with new ones. Should private buyers refuse to purchase the bonds at the interest rate set by the British government, those bonds can be sold to the Bank of England. The option to sell to the Bank of England provides a mechanism to prevent excessively high bond rates. The interest rate regulation (fixing bond prices) would also be achieved through the Government Debt Management Office by expanding that institution’s mandate (subject of a separate policy brief).

2. The size of the public debt is not a problem.

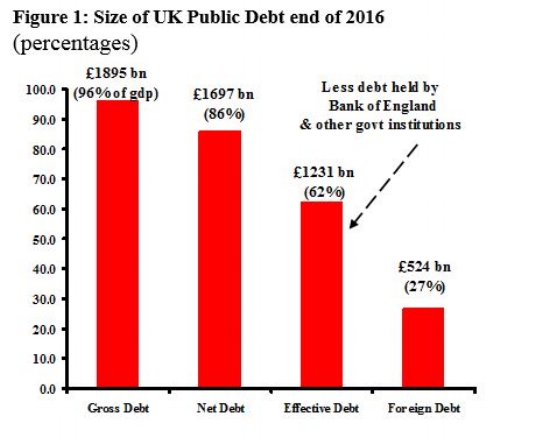

Figure 1 shows that outstanding public bonds or “gilts” amounted to £1.9 trillion or 96% of GDP at the end of 2016, which was the UK gross debt. Public sector liquid assets (eg cash deposits) reduced this to £1.7 trillion or 86% of GDP. This, the net debt, is the measure of public indebtedness used by the Treasury. About 27% of this amount (£466 bn) was held by public sector institutions, the vast majority by the Bank of England. When this debt, what the public sector owed itself, is subtracted we get the effective debt, the debt that the UK government owes to others. The effective debt was 62% of GDP, barely above the famous Maastricht 60% (which incorrectly refers to the gross debt).

Source: Office for National Statistics

Source: Bank of England

3. The public debt is not a burden.

The public sector itself owns 25% of the £1.9 trillion UK gross public debt (Figure 2). The government pays the interest on this portion of the debt to itself. Thus, one-quarter of the debt and the interest paid on it are not a burden. Pension funds hold a large portion of the 75% of gilts not owned by the government. The interest paid on debt held by pension funds is income to households. This is a source of household income, a benefit not a burden.

Debt held by the government itself and pension funds are long term holdings, rarely marketed. When these are subtracted the remaining gilts constitute the market-active public debt, £808 bn and well less than 50% of GDP at 45%. At the end of 2016 private corporate and foreign gilts holders owned 41% of gilts. Only the £524 bn of gilts held by foreign creditors could be considered a “burden” in that the associated interest payments are from UK taxpayers to non-UK creditors. For fiscal year 2015/16 interest payments to foreign creditors were approximately £12 bn, implying a quite small debt burden of 0.6% of GDP.

Policy Framework

Analysis of the nature, size and ownership of the UK public debt shows that it poses no threat to economic stability, its size is modest and its burden on taxpayers is minor. From this come the following policies.

- More public borrowing for investment and current expenditure is technical justified by the size of the debt.

- At the time of the general election of 2010 the share of foreign ownership of the UK debt was 15.6%. Under the coalition and Conservative governments foreign ownership rose to 26.5% of the total. The minor burden represented by foreign interest payments could be reduced by measures that would limit gilt sales to domestic buyers (applied in several other countries).

- While interest payments to domestic gilt holders are not a net burden to taxpayers, they may have a negative redistribution effect. Distributional regressivity could be eliminated through progressive income taxation.

- Should a Labour government face speculative pressure on gilt rates, this could be prevented by bond sales to the Bank of England or the proposed public sector interest bank. An expanded mandate for the Government Debt Office offers a third policy solution.

John Weeks is Professor Emeritus, SOAS, University of London, and associate of Prime Economics.

This policy brief may be downloaded as a pdf here